The Belgrade Offensiveis a crucial part of the turbulent drama of World War II; it was a historic battle that not only changed the path of history but also signaled Yugoslavia's freedom from Axis rule. The attack stands as a shining example of Allied resolve and unity in the annals of military strategy and international collaboration.

The capital of Yugoslavia, Belgrade, came under the ruthless control of Nazi Germanyand its allies while the war raged throughout Europe. The conflict for this strategically important city would come to represent defiance and fortitude in the face of oppression. A confrontation between a broad coalition of Allied forces and the Axis powers was imminent.

In this article, we will journey through the epic tale of the Belgrade Offensive, shedding light on its historical context, important players, and lasting legacy. From the meticulous planning and preparation to the heroic battles on the frontlines, from the tenacity of the Yugoslav partisans to the Allied forces' determined march.

Background Of Belgrade Offensive

By the summer of 1944, the Germans had not only lost control of practically all the mountainous areas of Jugoslavia but were no longer able to protect their essential lines of communication. Another general offensive on their front was unthinkable, and by September, it was clear that Belgrade and the whole of Serbia must shortly be free of them.

These summer months were the best the movement had ever seen; there were more recruits than could be armed or trained, and desertions from the enemy reached high numbers; one by one, the objectives of resistance were reached and taken.

Basil Davidson

Early in September 1944, Army Group E (the southern region of operations) and Army Group F (the northern area of operations) of the German Army were stationed in the Balkans (Yugoslavia, Greece, and Albania).

Army Group E was ordered to retire into Hungary in reaction to the Red Army's advance into the Balkans and the defeat of German forces in the Jassy-Kishinev Operation, which compelled Bulgaria and Romania to switch sides. Army Group F components were used to form Army Group Serbia, another Army Group in Hungary.

Following the 1944 Bulgarian coup d'état, the country's monarchist/fascist administration was toppled and replaced by a Fatherland Front government headed by Kimon Georgiev. Following the election of a new government, Bulgaria declared war on Germany.

Four armies in Bulgaria, totaling 455,000 soldiers, were mobilized and restructured under the new pro-Soviet administration. Three armies of Bulgaria, with around 340,000 soldiers, were stationed along the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border at the beginning of October 1944.

Marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin's Red Army 3rd Ukrainian Front forces had gathered along the Bulgarian-Yugoslav border by the end of September. The Bulgarian 2nd Army (General K. Stanche commanding under the operational leadership of the 3rd Ukrainian Front) was stationed to the south on the Niš rail line at the intersection of the Bulgarian, Yugoslav, and Greek borders, while the Soviet 57th Army was positioned in the Vidin region.

This further prompted the Partisans' 1st Army to go into Yugoslavia and help their 13th and 14th Corps, which were involved in the liberation of Niš and the 57th Army's push into Belgrade, respectively. The 46th Army of the Red Army 2nd Ukrainian Front was stationed near the Teregova River in Romania, ready to destroy the rail connection that connects Belgrade and Hungary north of Vršac.

Marshal Josip Broz Tito, the leader of the Yugoslav Partisans, and the Soviets coordinated pre-operations. On September 21, Tito landed in Romania under Soviet authority. He then took a plane to Moscow, where he met Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. The fact that the two sides were able to come to a consensus over Bulgarian forces' involvement in the operation that would take place on Yugoslav soil made the meeting successful.

First Stage Of The Belgrade Offensive

The Soviet 17th Air Army (3rd Ukrainian Front) was instructed to obstruct the German soldiers' departure from Greece and southern Yugoslavia before the commencement of ground combat. In order to do this, airstrikes were conducted against railway bridges and other significant infrastructure in the districts of Niš, Skopje, and Krusevo between September 15 and September 21.

Plan Of The Offensive

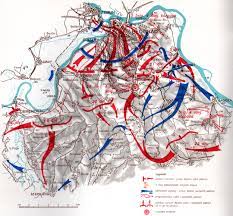

The Yugoslavs would need to breach German defensive positions on the border between Yugoslavia and Bulgaria in order to seize control of the highways and mountain passes across eastern Serbia, assault the Great Morava Valley, and establish a bridgehead on the west side. The Yugoslav XIV Corps was instructed to assist the Red Army attack behind the lines, with the 57th Army being assigned the primary job of carrying it out.

Following the first phase's successful conclusion, the 57th Army's 4th Guards Mechanized Corps was supposed to be sent to the beachhead on the West Bank. This corps, with its tanks, heavy weaponry, and superior firepower, was a good match for the Yugoslav I Corps, which was mainly equipped with light infantry but had a large concentration of men.

These two units were supposed to join and launch the major southerly onslaught upon Belgrade. This strategy had the benefit of allowing for quick deployment during the crucial last phases of the attack and allowing for the isolation of the German forces from the main forces in eastern Serbia.

Local Situation In Eastern Serbia

The occupiers and auxiliary forces forced partisans to leave northern, eastern Serbia in January 1944. Germans commanded the Bulgarian garrison, part of the German police, and the Serbian Quisling army, while Chetnik soldiers, mainly allied with the Germans, remained. In July and August 1944, the 23rd and 25th Partisan Divisions returned to central-eastern Serbia.

They established a makeshift airport at Soko Banja to create an accessible area for arms and ammunition aviation. This secured supplies and allowed residents to flee—hurt persons. Northern eastern Serbia became more critical for both parties after the Romanian takeover. The Partisans were quicker and better positioned in each race.

During the battle for Zajecar and Negotín, the 23rd Division defeated the Order Police battalion and auxiliaries, while the 25th Division failed to attack Donzi Milanovac.

Many volunteers joined units, increasing their size. The 45th Serbian Division was constituted on September 3rd, while XIV Corps Headquarters was established on September 6th as the supreme authority for the area of operations. Germans with the 1st Mountain Division entered Zajecar on 9 September.

The Partisans attacked Negotin for a week to block German Danube access. After the Red Army failed to penetrate Romania on September 16, the XIV Corps abandoned Danube shoreline protection and attacked German forces elsewhere.

On September 12, a NOVJ delegation commanded by Colonel Ljubodrag Đurić crossed the Danube to Romania and made contact with the Red Army's 74th Rifle Division at Negotin. The 1st Battalion of the 9th Serbian Brigade entered Romania with the delegation. The 109th Regiment of the 74th Rifle Division was the 1st Battalion's opponent until October 7.

Army Group F Commander Feldmarshall Maximilian von Weichs ordered a Serbian Partisan task group in August 1944. It featured the 4th SS Police Division, 1st Mountain Division, 92nd Motorized Regiment, 4th Brandenburg Regiment, 191st Assault Brigade, and 486th Armored Reconnaissance Division.

After the events in Romania and Bulgaria, Hitler sent the 11th Air Field Division, 22nd Infantry Division, 117th Division, 104th Jaeger Division, and 18th SS Mountain Police Regiment into Macedonia. After fighting Montenegrin partisans, the 1st Mountain Division moved to Nis. On September 6, General Hans Felber took charge and ordered it to control the Bulgarian border.

The division took Zajecar and reached the Danube by mid-September when a big offensive was planned. The 2nd Panzer Army's 7th SS Division assaulted eastern Bosnian and Sanddjak partisans entering Serbia. On September 21, General Felber took command of the division to attack western Serbian partisans. The raid was canceled owing to worsening eastern border conditions.

From late September, the division guarded the southern Serbian border between Zajecar and Vranje in southeastern Serbia. This let the 1st Mountain Division focus on the north, between Zajecar and the Iron Gate. The 92nd Motorized Regiment, 2nd Brandenburg Regiment, and 18th SS Mountain Police Regiment strengthened the 1st Mountain Division.

Local soldiers and some German troops retreating from Romania and Bulgaria strengthened both divisions. On 22 September, the 1st Mountain Division attacked the left side of the Danube to take the Iron Gate, while the Red Army 75th Corps attacked in the other direction.

Second Stage Of Belgrade Offensive

Attack Of The 57th Army

Following the Second Jassy-Kishinev Offensive, the German forces and the Red Army rushed to cross the "Blue Line." This front line, which stretched along the Iron Gates from the southern Carpathian mountains to the boundary between Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, was strategically significant. In striking contrast to the 91 Rifle Divisions in the last attack, by late September, the 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts were able to deploy about 19 Rifle Divisions to this line.

However, the German assault was hindered by rugged terrain, broken roads, logistical problems, and uncertainty about the local forces. The Red Army's concentration of forces proved more effective, and by the end of September, they had gained numerical dominance. This, together with the possibility of working with the NOVJ (Yugoslav Partisans), contributed to the beginning of the offensive.

On September 12, the 75th Rifle Corps reconnaissance forces were the first to arrive in the Iron Gates region and make contact with the Yugoslav Partisans across the Danube.

But German forces drove the Partisans back and launched a narrow assault on the other side of the river. Although the original intention was for the 75th Corps to become part of the 57th Army later, German aggressiveness and unstable situations forced them to cross the Danube on September 22.

The German 1st Mountain Division then counterattacked, driving the Soviets back to the banks of the Danube. Reinforcements arrived overnight, and on September 27 and 28, the 57th Army began an attempt to recover momentum.

This offensive was carried out by three Army Corps, giving the Red Army the advantage over the German solid defense. After the liberation of Negotin on September 30, violent clashes broke out in Zaječar.

Army Group F Command ordered the 104th Jäger Division to join in order to strengthen the front, but partisan activity and transportation issues prevented them from arriving. In response, the 92nd Motorized Brigade and the 1st Mountain Division launched a defensive attack to gain time.

The Red Army gradually took over and drove the Germans to retreat despite clashes and formidable German fortifications. By early October, the German soldiers were split up into three incomprehensible combat groups. Delaying a decisive offensive, the Red Army chose to use mobile units to take advantage of wide highways in order to penetrate further.

The 5th Guards Motorized Rifle Brigade seized a bridgehead on the west side of the Great Morava River on October 7th by making a swift movement that avoided German frontline units. Concurrently, on October 10, the 93rd Rifle Division managed to take control of a vital river bridge.

By October 12, the 4th Guards Mechanized Corps had arrived in Natalinci and was creating, with the Yugoslav 1st Proletarian Corps, the primary strike force for the direct assault on Belgrade. The offensive's initial phase was successful, as the Red Army made substantial progress toward the "Blue Line."

German Counter-Measures

When the German command structure was reformed on October 2, General Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller, the previous commander of the German troops in Crete, took over the front south of the Danube.

Kraljevo was his corps headquarters. General Wilhelm Schneckenburger managed the soldiers north of the Danube and defended Belgrade immediately. General Felber's Serbian Army Detachment under the Supreme Commander of the South-East (Army Group F) commanded both corps. As the conflict escalated in Belgrade, Army Group F headquarters relocated to Vukovar on October 5.

Felber and Schneckenburger stayed in Belgrade. Army Group F Command confirmed on October 10 that the Red Army had penetrated the Great Morava Valley through a front hole. These Soviet forces attacked Belgrade directly, cutting off the 1st Mountain Division in eastern Serbia and threatening a rear strike. The German command wanted to narrow the hole with a counterattack, but it needed more strength.

The German headquarters had to call for 2nd Panzer Army soldiers when southern reinforcements failed. The 2nd Panzer Army lost several cities, including Drvar, Gakko, Prijedor, Jajce, Donzi Vacch, Bugoino, Gorny Vacch, Tuzla, Hvar, Brac, Peljesac, Belane, Nikšić, Bireça, Trebinje, Benkovac, Libno, and temporary ones like Zvornik, Darvar, Pakcu, Kolasin, Bijelo Polje, Banja Luka, Pljevlja, and others.

A revised defense strategy, adopted on October 10, caused the 2nd Panzer Army to evacuate part of the Adriatic coast and establish a new defensive line eastward from the Zurmanya mouth, using mountains and defended cities. Now possible. Three "corps" divisions (369th, 373rd, and 392nd) and two divisions (118th and 264th) for German deployment in vital locations were to hold this line of defense.

Due to the collapse of the 369th Division, only two battalion-strong combat groups of the 118th Division were dispatched to Belgrade. At the same time, the 8th Yugoslav Corps attacked the 264th Division and destroyed it near Knin.

Activities On The Flanks

In the southern flank of the front, the Bulgarian 2nd Army attacked Leskovac Niš and fought the 7th SS Mountain Division "Prinz Eugen" very immediately. Yugoslav partisans helped the army beat a Chetnik and Serbian Frontier Guard unit and occupied Vlasotince two days later. Bulgarian soldiers attacked German fortifications at Vera Palanka on 8 October and reached Vlasotintse two days later with an armored brigade.

On October 12th, the armored brigade (backed by the 47th Partisan Division's 15th Brigade) captured Leskovac, and a Bulgarian reconnaissance battalion crossed the Morava River to reconnoiter Niš. The Bulgarian 2nd Army's capture of Kosovo would lead to German Army Group E's departure, not the 'Prinz Eugen' division's retreat to the northwest.

The road north will be closed from Greece. The leading Bulgarian army entered Kursumliya on October 17 and went to Kursumlyaska Banja. With severe casualties, the brigade crossed the Preporak Pass on 5 November and took Podjevo before reaching Pristina on 21 November.

The 46th Army, reinforced by the Red Army's 2nd Ukrainian Front, attacked on the northern flank. Block the Tisza River river and rail supply routes and surround the German positions in Belgrade from the north.

With the help of the 5th Air Force, the 10th Guards Rifle Corps swiftly crossed the Tamis and Tisza rivers north of Pančevo, threatening the Belgrade-Novi Sad railway. Further north, the Red Army's 31st Guards Rifle Corps moved on Petrovgrad, while the 37th crossed the Tisza River to threaten the Novi Sad-Subotica railway line. Ready to attack Budapest strategically.

Assault On Belgrade

On October 14, the German resistance was broken south of Belgrade by the Yugoslav 12th Corps and the Red Army's 4th Guards Mechanized Corps, which advanced into the capital. While the Red Army was battling on the edges of the northern bank, the Yugoslavs were moving south of the Sava River along the highways into Belgrade.

The withdrawal of forces to eliminate thousands of enemy troops around Belgrade and Smederevo (to the southeast) caused a delay in the city's assault. Joint Soviet and Yugoslav forces had taken total control of Belgrade on October 20.

From the southeast, the Bulgarian 2nd Army and the Yugoslav 13th Corps moved together. They were in charge of Leskovac and the Niš region. Along the South and Morava rivers, the soldiers were also in charge of shutting off the primary route for Army Group E's departure.

As a result, Army Group E was unable to reinforce the German forces in Hungary and was forced to retreat over the mountains of Bosnia and Montenegro. Parts of the 3rd Ukrainian Front eventually severed the Thessaloniki route to Belgrade the next day when they assaulted Kraljevo.

Along with Yugoslav Partisan soldiers crossing the Danube, the Soviet 10th Guards Rifle Corps of the 46th Army (2nd Ukrainian Front) offered more offensive might from the northeast against the Wehrmacht's position in Belgrade. They captured Pančevo after clearing the left bank of the Tisa and Danube in Yugoslavia.

Allied Forces Participating In The Attack

Forces taking part in the siege on the Yugoslav capital were:

The Soviet Union

The Soviet Union, under Marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin, sent substantial forces that were instrumental in the Belgrade Offensive. Among the essential formations were the 292nd Guards Self-Propelled Artillery Regiment, the 13th to 15th Guards Mechanized Brigades, the 36th Guards Tank Brigade, and the 4th Guards Mechanized Corps.

The 57th Army was commanded by General Nikolai Gargen and consisted of the 75th Rifle Corps, which included divisions such as the 223rd and 236th Rifle Divisions. In addition, the Air Army, several Aviation Divisions, the Armored Boat Brigade, and the Soviet Danube Military Fleet all had crucial roles to play in the operation.

Yugoslavia

Lieutenant-Colonel Peko Dapcevic led the 1st Army Corps, which was comprised of divisions including the 1st Krajina Division, 16th Vojvodina Division, 28th Slavonian Division, and 36th Vojvodina Division. Yugoslavia provided its division for the army corps.

Bulgaria

Bulgaria actively participated with its 1st Army, Second Army, and 4th Army under leaders like Vladimir Stoichev and Kirill Stanchev. By the end of September, these troops had engaged Yugoslav rebels in brutal combat against the Germans along the Bulgarian-Yugoslav border.

Some 340,000 Soviet soldiers surrounded them. With Lieutenant General Vladimir Stoychev leading from 1944 to 1945, the 1st Army moved into Serbia, Hungary, and Austria in cooperation with the Red Army in 1945 despite difficult circumstances and heavy casualties.

Aftermath Of Belgrade Offensive

The German defenders faced a severe problem when the 57th Army and the Yugoslav 51st Division completed the Belgrade operation in November and took control of the bridgehead at Baranja on the Danube's left bank. For the Budapest operation, the 3rd Ukrainian Front forces were massively concentrated at the bridgehead.

Up to mid-December, the Red Army 68th Rifle Corps engaged in combat on both the Syrmian Front and the Kraljevo bridgehead. After that, they were sent to Baranja. Up to the end of December, the Red Army Air Force Group "Vitruk" supported the Yugoslav Front from the air.

For almost 100 kilometers, the Yugoslav 1st Army Corps pushed German forces westward via Srem, where the Germans were able to establish a front by mid-December.

German Army Group E was obliged to struggle for a way through the mountains of Sandžak and Bosnia after losing Belgrade and the Great Morava Valley; its first echelons did not reach Drava until mid-February 1945.

Commemoration Of The Battle

On June 19, 1945, the Supreme Soviet Presidium established the Medal "For the Liberation of Belgrade". The Yugoslav People's Army conducted its second military parade on Revolution Boulevard (now King Alexander Boulevard) to commemorate the offensive's first anniversary.

In SFR Yugoslavia and the Republic of Serbia, there have only been two military parades and high-level celebrations since then. The first, the March of the Victor, was held on Nikola Tesla Boulevard with Russian President Vladimir Putin as the guest of honor.[40]

Russian presidents or other high-ranking officials visit Belgrade during every jubilee anniversary.

Beginning with Dmitry Medvedev in 2009 and continuing with Vladimir Putin, the Presidents of Serbia and Russia lay wreaths at the Liberators of Belgrade Memorial, which contains the remains of over 3,500 Yugoslav Partisans and Red Army soldiers who died during the offensive. Prime Minister Medvedev represented Russia at the 75th anniversary festivities in 2019 instead of Putin.

Belgrade Offensive - FAQs

Was Belgrade Captured In 1941?

On April 13, 1941, Belgrade fell under occupation; four days later, Yugoslavia submitted.

When Did The Belgrade Offensive Start?

Belgrade Offensive began on September 14, 1944.

Was Belgrade Bombed During WW2?

Belgrade's infrastructure was bombarded four times in September 1944, twice in May, thrice in June and July, and three times in April 1944.

Conclusion

The Belgrade Offensive shows Allied perseverance, commitment, and collaboration during World War II. This massive assault freed Yugoslavia and shaped the European conflict. The strategic race to the "Blue Line" showed the Red Army's ability to move and cooperate with local Yugoslav Partisans, helping them overcome rugged terrain and stubborn German opposition.

The Belgrade Offensive symbolizes freedom's victory over oppression and marked a turning point in the war against the Axis forces beyond its military goals. This chapter in history represents the tenacity of individuals who struggled for justice and freedom in the darkest days of the 20th century.